Fidelity National Bank & TC, Kansas City, MO (Charter 11344)

Fidelity National Bank & TC, Kansas City, MO (Chartered 1919 - Liquidated 1933)

Town History

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the most populated municipality of the Kansas City metropolitan area, which straddles the Kansas–Missouri state line and has a population of 2,392,035. Most of the city lies within Jackson County, with portions spilling into Clay, Cass, and Platte counties. Kansas City was founded in the 1830s as a port on the Missouri River at its confluence with the Kansas River coming in from the west. On June 1, 1850, the town of Kansas was incorporated; shortly after came the establishment of the Kansas Territory. Confusion between the two ensued, and the name Kansas City was assigned to distinguish them soon after.

The city is composed of several neighborhoods, including the River Market District in the north, the 18th and Vine District in the east, and the Country Club Plaza in the south. Celebrated cultural traditions include Kansas City jazz; theater, as a center of the Vaudevillian Orpheum circuit in the 1920s; the Chiefs and Royals sports franchises; and famous cuisine based on Kansas City-style barbecue, Kansas City strip steak, and craft breweries. It serves as one of the two county seats of Jackson County, along with the major suburb of Independence. Other major suburbs include the Missouri cities of Blue Springs and Lee's Summit and the Kansas cities of Overland Park, Olathe, Lenexa, and Kansas City, Kansas.

Kansas City had 43 National Banks chartered during the Bank Note Era, and 40 of those banks issued National Bank Notes.

Bank History

- Organized April 28, 1919

- Chartered May 1, 1919

- Conversion of Fidelity Trust Company of Kansas City

- Assumed 11037 by consolidation May 13, 1919 (National City Bank, Kansas City, MO) and assumed its circulation

- Assumed 12686 by consolidation December 31, 1928 (New England NB & TC (No Issue), Kansas City, MO)

- Absorbed 10039 July 10, 1930 (Commonwealth NB/Liberty NB, Kansas City, MO)

- Conservatorship March 13, 1933

- Liquidated November 24, 1933

- Succeeded by 13736 (Union National Bank (No Issue), Kansas City, MO)

Fidelity Trust Company of Kansas City

In June 1887, Mr. James A. Blair, was president of the Comanche County Bank in Coldwater, the First National Bank at Medicine Lodge, and also of the Fidelity Trust Company of Kansas City, the wealthiest incorporated company in the west. Mr. Oliver C. Ewart was cashier of the First National Bank of Medicine Lodge and a director in the Fidelity Trust Company. The firm of Blair, Ewart & Co. was the most successful firm of bankers in the southwest. They were principal stockholders in each of the following banks: First National Bank of Garden City, First National Bank of Meade Center, First National Bank of Ashland, Comanche County Bank of Coldwater, and First National Bank of Medicine Lodge.[3] On November 25, 1887, the secretary of state issued certificate of incorporation to the Fidelity Trust Company of Kansas City, capital stock $100,000, all paid up. The incorporators were James A. Blair, James L. Lombard, George Sheidley, Thomas B. Tomb, of Kansas City; O.C. Ewart, Medicine Lodge, Kansas; B. Lombard, Jr., of Boston, Mass.; and James I. Blair of Blairstown, New Jersey.[4]

In April 1888, the officers of the Fidelity Trust Company were James A. Blair, president; Geo. Sheidley, vice president; and Jas. H. Frost, secretary. The directors were John L. Blair, Jas. L. Lombard, George Sheidley, O.C. Ewart, B. Lombard, Jr., and James A. Blair. The company was located at 46 Sheidley Building, Kansas City, Missouri.[5]

In June 1899, the Fidelity Trust Company, capitalized at $500,000, was incorporated in Kansas City. Henry C. Flower of Kansas City would be president.[6]

In July 1911, the Fidelity Trust Company appointed two additional vice presidents, Thornton Cooke and F.C. Cochran, who would assume their duties on the 15th. Mr. Cooke had been with the company nine years and in becoming vice president he retained his position as treasurer. Mr. Cochran was cashier of the First National Bank of Plainville, Kansas and retained holdings in several Kansas banks. Mr. Cochran was a graduate of the Kansas University in 1900. He was the son of C.G. Cochran of Plainville, a merchant and banker. For the past three years, he had been in the real estate loan business in Kansas City in the firm of Baird & Cochran and now was in charge of the real estate loan department of the Fidelity Trust Company. President Henry C. Flower had been gathering young men of exceptional ability and quickly discovered the requisite qualification in Forrest C. Cochran.[7]

In February 1913, the officers of the Fidelity Trust Company were Henry C. Flower, president; Charles Campbell, 1st vice president; George W. Fuller, 2d vice president; Henry C. Brent, 3rd vice president; Thornton Cook, Forrest C. Cochran, vice presidents; Frank Hagerman, counsel, W.F. Comstock, secretary; A.D. Rider, treasurer; H.H. Mortin, bond officer; H.B. Leavens, trust officer; and C.W. Ogden, mgr., safe deposit dept. The company had capital $1,000,000 and surplus $1,000,000.[8]

On May 10, 1919, George Washington Fuller passed away in Kansas City. He was educated in the common schools in Illinois until he was 15. In 1869 he came to Kansas City. In 1870 he became employed as a traveling salesman by Deere, Mansur & Co., a wholesale dealer in agricultural implements and farm machinery. After building up the business as a traveling salesman, Fuller was made manager in 1882 and continued in that position until 1889. At this time the firm dissolved, and the John Deere Plow Company was incorporated, into which he was elected secretary and manager. He was associated with the business until 1904, when he sold his interest. While being in the agricultural implements and farm machinery business, Fuller made advancements in business circles. In 1905 he was elected as vice president of the Fidelity Trust Company and was a director and member of the executive committee. He also was a director and one of the incorporators of the Traders National Bank and the Produce Exchange Bank since their organization. He was a veteran of the Civil War enlisting in April 1864 in the 139th Illinois Infantry, serving until the following October.[9]

Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company (Charter 11344)

In May 1919, the new Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company was formed from the consolidation of the Fidelity Trust Company and the National City Bank of Kansas City.[10] The officers were Henry C. Flower, chairman; John M. Moore, president; W.D. Johnson, Geo. T. Tremble, Chas. H. Moore, Lester W. Hall, E.E. Ames, D.A. McDonald, and A.D. Rider, vice presidents; J.F. Meade, cashier; A.H. Smith, Douglas Wallace, J.C. Williams, D.M. Connor, Robert Johnson assistant cashiers; D.H. Martin, manager, bond dept.; and R.D. Slaymaker, managers, safe deposit Dept. The capital was $2,000,000 and surplus $1,000,000.[11] Joe C. Williams, formerly vice president of the Bank of Commerce, Springfield, Missouri, was elected assistant cashier of the new Fidelity National Bank and Trust company following the recent consolidation.[12]

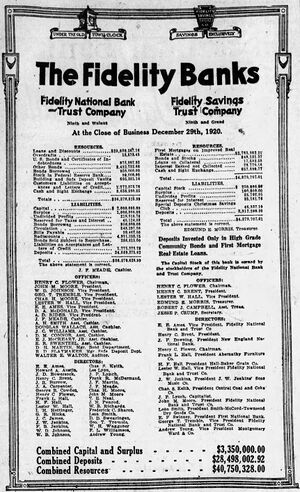

In January 1921, the Fidelity Banks consisted of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company at Ninth and Walnut and the Fidelity Savings Trust Company at Ninth and Grand. The officers of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company were Henry C. Flower, chairman; John M. Moore, president; W.D. Johnson, Geo. T. Tremble, Chas. H. Moore, Lester W. Hall, E.E. Ames, D.A. McDonald, and A.D. Rider, vice presidents; J.F. Meade, cashier; A.H. Smith, Douglas Wallace, J.C. Williams, D.M. Connor, E.J McCreary, and E.R. Swentzel, assistant cashiers; D.H. Martin, Mgr., bond department; R.D Slaymaker, mgr., safe deposit dept.; Walter E. Walton, auditor. The directors were E.E. Ames, Howard A. Austin, J.D. Bowersock, Henry C. Brent, J.R. Burrow, J.A. Carpenter, George R. Cowden, Henry C. Flower, Frank L. Hall, H.F. Hall, Lester W. Hall, I.H. Hettinger, G.R. Hicks, J.C. James, J.W. Jenkins, F.B. Jenkins, W.D. Johnson, W.B. Johnson, Chas. S. Keith, Lee Lyon, J.P. Lynch, Frank R. McDermand, J.F. Martin, J.F. Meade, Chas. H. Moore, John M. Moore, T.E. Neal, J.N. Penrod, W.B. Richards, Frederick C. Sharon, Leon Smith, D.D. Swearingen, Geo. T. Tremble, W.H. Waggoner, F.L. Williamson, and Andrew Young. Officers of the Fidelity Savings Trust Company were Henry C. Flower, chairman; Henry C. Brent, president; Lester W. Hall, vice president; Edmund E. Morros, treasurer; Robert J. Campbell, assistant treasurer; and Jesse P. Crump, secretary.[13]

In April 1924, Lester W. Hall was chosen president of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company to succeed John M. Moore.[14]

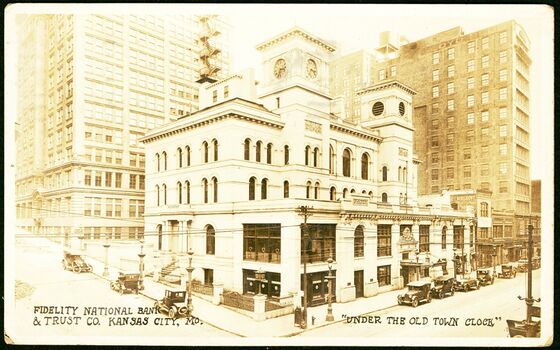

On December 20, 1928, stockholders of the New England National Bank and Trust Company in Kansas City met to take action with reference to the proposed consolidation with the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company. Joseph R. Bruce was president.[15] The consolidation became effecting at the close of business, December 31, 1928. All business would hereafter be transacted at the banking house of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company, southeast corner of Ninth and Walnut Streets in Kansas City.[16]

In 1931 the Fidelity National Bank & Trust Company built its new building (referred to locally as the Fidelity Building) at an estimated cost of $2.85 million, including bank fixtures. 909 Walnut (formerly Fidelity National Bank & Trust Building, Federal Office Building and 911 Walnut) is the twin-spired, 35-story, 471-foot residential skyscraper in Downtown Kansas City, Missouri. It was Missouri's tallest apartment building until the conversion of the Kansas City Power & Light building and the tenth-tallest habitable building in Missouri. The site had previously been a two-story post office and federal building until 1904, when Fidelity purchased the site for its headquarters. The two-story building was razed in 1930.

In June 1938, Henry C. Flower, retired Kansas City banker, died in Greenwich, Connecticut.[17]

Union National Bank (Charter 13736)

On March 14, 1933, the Fidelity National Bank & Trust Company, the Fidelity Savings Bank, and the Missouri Savings Bank reopened under restrictions limiting withdrawals to 5%.[18] On May 10th, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation took action to reopen two large banks, one in Kansas City, Missouri and the other in Indianapolis and through them to ease the situation for many smaller banks. The corporation agreed to purchase $1,500,000 of preferred stock of the National Bank of Kansas City which would take over the assets of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company. The latter institution had been closed since the banking holiday. The purchase was conditional upon the sale of $1,500,000 of common stock to stockholders, depositors and other citizens of Kansas City.[19] On Monday, July 24, 1933, reorganized Fidelity banks opened as the Union National Bank in Kansas City (Charter 13736).[20] The new national bank occupied the Fidelity Building, southeast corner of Ninth and Walnut, on a rental basis. The bank was a member of the Federal Reserve and the Kansas City Clearing House. The directors were Howard A. Austin, general agent, Prudential Insurance Co.; Justin D. Bowersock, Bowersock, Fizzell and Rhodes, attorneys, H.F. Hall, retired; George R. Hicks, president; Irving Hill, president, Lawrence Paper Mfg. Co.; Herbert V. Jones, real estate mortgage loans; H.M. Langworthy, Langworthy, Spencer and Terrell, attorneys; J.J. Flynn, president, U.S. Epperson Underwriting Co.; T.H. Mastin, T.H. Mastin & Co., reciprocal insurance; and Joseph F. Porter, president, Kansas City Power & Light Co. The officers were George R. Hicks, president; D.A. McDonald, George G. Moore, and Robert J. Campbell, vice presidents; R.B. Hewitt, vice president & trust officer; E.J. McCreary, Jr., cashier; Douglas Wallace, assistant vice president; Albert H. Smith, R.J. Bushman, and D.M. Connor, assistant cashiers.[21]

In November 1968, Directors of two long-established Kansas City banks, Columbia National and the Union National have agreed in principle to a merger that would create one institution with total resources of more than $90 million, making it the fourth largest bank in Kansas City. The announcement was made by Charles L. Aylward, chairman of Columbia, and W. Ralph Warner, chairman of Union, who said the consolidation would be effected by an exchange of the present stock of the two banks into stock of the new bank, which would be called the Columbia Union National Bank and Trust Company. Warner was slated to be chairman and Aylward president of the new bank. The merger, according to the announcement, is subject to approval by stockholders of the two banks and appropriate federal supervisory authorities. A majority of the Union National stock was purchased last February by the Layco Investment Company, a group of Kansas City investors who acquired their interest after a tender offer. Resources of Union National were more than $48 million and those of Columbia National in excess of $44 million. Combined funds on deposit at the banks totaled nearly $79 million and total loans outstanding at the banks amounted to about $37 million. The banks had a combined capital and surplus of about $10 million. This would give them a maximum loan limit, as a consolidated bank, of about 1 million dollars, a limit that is far beyond that which each could have loaned separately. One of the largest, oldest and never-merged banks in Kansas City, Columbia National opened its doors in 1919 and since had grown in assets to the 13th largest bank in the metropolitan area. Union National opened in 1933 during after the bank moratorium, formed to take over the operation of the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company. After some time the new Union bank was able to pay back depositors $1.09 for each dollar they had in the Fidelity. The Union National ranked about 11th in total assets among banks in the metropolitan area. Paul Ross, the vice chairman of the board of Union and Sydney M. Cooke, Sr., president of Columbia, would become vice chairman of the board of Columbia Union. L.A. Laybourn, chairman of the executive committee of Union, chairman of the board of Mid-Continent bank, and president of the Layco Group, would become chairman of the executive committee of the new bank.[23]

On September 9, 1969, directors of the two banks and stockholders in separate meetings ratified the consolidation. With no objection from the Justice Department to the approval of the comptroller of the currency, a green-light was given for the formation of the fourth largest commercial bank in Kansas City. The new bank was located at 900 Walnut Street in the completely renovated and modernized building formerly occupied by Union National. Commercial functions of Columbia Union would begin on September 15th. Under terms of the merger, the shareholders of Union National received 250,000 shares of common stock on a share-for-share basis and initially would own 84.76% of the outstanding common stock. Columbia National shareholders received 40,000 shares of $85 par value non-voting convertible preferred and 45,000 shares of common stock. Each share of Columbia common would receive on share of preferred and 1 2/8 shares of common. The preferred was convertible into 1 3/8 share of common after an 8-year period.[24]

In September 1977, Hugh G. Hadley of the Kansas City Times wrote the following article. It's a familiar scene at the Kansas City post office on Pershing Road-a patron, perhaps searching for the wastebasket or a dropped article lets his eyes linger on the unusually ornate scrollwork on the eight tables in the lobby. Then wrinkles his brow and perhaps his lips move, as he spells out the letters "F.N.B. & T." "They all try to figure it out, and try to read U.S. in there, but it's just not there," says Joe Heydon, director of the customer service division. "They're classics, really beautiful, and we've had a lot of inquiries about them." The beautifully inscribed brasswork goes back almost to the building's beginning, in fact, even predates the building, for the eight lobby tables were bought for the post office by the predecessor of General Services Administration soon after the structure was built in 1931. The letters stand for the Fidelity National Bank & Trust Company, which in 1931 had just moved into its own new twin-tower structure at the southeast corner of 9th and Walnut. The bank, the outgrowth of several earlier institutions, became a victim of the Depression and closed its doors in July 1933. Its assets became a part of a new Union National Bank, now the Columbia Union Bank. The hand-tooled bronze tables of an ornateness and quality not seen today were a special source of pride for Henry C. Flower, organizer and first president of the Fidelity, and of George R. Hicks, president of the Union National in 1933. So were the Fidelity Bank Singers, a chorus of 12 under the leadership of Clarence Sears which sang for the Chamber of Commerce and at other functions. So was the high, colorful ceiling with its figures of eagles and horns of plenty and the signs of the zodiac in rose and gold on marble. The architect said there was no symbolism involved--just a modernized classical design. The Fidelity wanted to do things right, so, along with the hand-tooled check desks, it promoted Mrs. Kathryn Edinger Berkley to be assistant cashier in charge of the women's department, a concession to the burgeoning role of women in business affairs. The building went up with the town clocks in its twin towers, carrying on a tradition of the earlier building on that site, housing the post office, the Fidelity Trust Company and a $3,000 clock from the Howard Watch Company of Boston, with a 3,600 pound bell in another tower. The brass check desks were bordered with slots for checks, deposit and withdrawal slips and other bank necessaries which puzzled many postal patrons. The desks were prized by a longtime postal official, Herschel C. Ressler, whose card read on retirement in 1959: "Address: Ressler's Retreat. Occupation: Matching wits with Ozark fish." Herschel Ressler was a post office activist, and a former semipro baseball player who took over third base for the old Kansas City Red Sox after graduation from Manual High in 1908. He entered the postal service in 1914, served in World War I and later was commander of American Legion post 180, of postal employees. Ressler pushed baseball and bowling for postal employees and was president of the National Association of Postal Supervisors in 1933.[25]

On January 4, 1982, the Columbia Union National Bank & Trust Co., 900 Walnut Street, changed its name to Centerre Bank of Kansas City. Its parent company, First Union Bancorporation, became Centerre Bancorporation. The name change for Missouri's largest bank holding company and each of its affiliate banks also includes the National Bank in North Kansas City, First National Bank of Independence, First National Bank of Liberty and Centerre's lead bank, First National Bank in St. Louis.[26]

In the 1980s, Boatmen's Bancshares became the largest bank group in Missouri with the acquisition of Centerre Bancorporation. In 1981, it moved its headquarters to the 31-story Boatmen's Bank Building in Downtown St. Louis. In December 1988, the Boatmen's Bank banners went up on Centerre Bank branches as the two banks prepared to merge with federal regulatory approval anticipated in February 1989. Boatmen's acquisition of Centerre was official on Friday, December 9th for the two holding companies, but the individual banks in Springfield, St. Louis, Kansas City and Cape Girardeau awaited federal approval. Eventually, Boatmen's officials planned to close two Centerre branches in Springfield. The downtown bank at 300 S. Jefferson Avenue and an east Springfield location at 3020 E. Sunshine Street were close to a current Boatmen's facility and thus slated to close.[27]

Official Bank Title

1: Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company of Kansas City, MO

Bank Note Types Issued

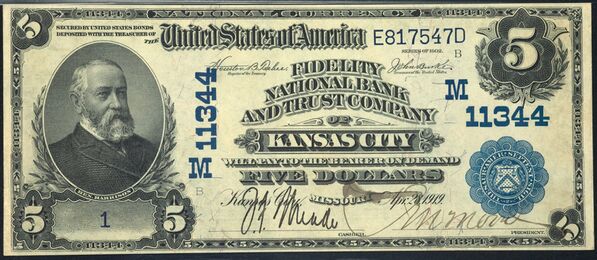

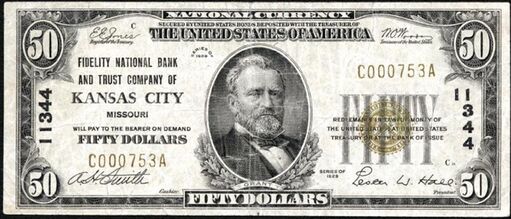

A total of $4,926,200 in National Bank Notes was issued by this bank between 1919 and 1933. This consisted of a total of 672,742 notes (555,760 large size and 116,982 small size notes).

This bank issued the following Types and Denominations of bank notes:

Series/Type Sheet/Denoms Serial#s Sheet Comments 1902 Plain Back 4x5 1 - 138940 1929 Type 1 6x10 1 - 9358 1929 Type 1 6x20 1 - 8831 1929 Type 1 6x50 1 - 862 1929 Type 1 6x100 1 - 446

Bank Presidents and Cashiers

Bank Presidents and Cashiers during the National Bank Note Era (1919 - 1933):

Presidents:

Cashiers:

Other Known Bank Note Signers

- Elmer Ellsworth Ames, Vice President, 1919]

- George T. Tremble, Vice President, 1919...1921

- Joseph Campbell Williams, assistant cashier 1919

Bank Note History Links

- Fidelity National Bank & TC, Kansas City, MO History (NB Lookup)

- Missouri Bank Note History (BNH Wiki)

Sources

- Kansas City, MO, on Wikipedia

- Don C. Kelly, National Bank Notes, A Guide with Prices. 6th Edition (Oxford, OH: The Paper Money Institute, 2008).

- Dean Oakes and John Hickman, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes. 2nd Edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 1990).

- Banks & Bankers Historical Database (1782-1935), https://spmc.org/bank-note-history-project

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Thu., Jan. 6, 1921.

- ↑ The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Jan. 1, 1928.

- ↑ Kingman Morning News, Kingman, KS, Wed., June 1, 1887.

- ↑ Jefferson City Tribune, Jefferson City, MO, Sat., Nov. 26, 1887.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Apr. 8, 1888.

- ↑ Allen County Democrat, Iola, KS, Fri., June 30, 1899.

- ↑ Plainville Gazette, Plainville, KS, Thu., July 20, 1911.

- ↑ The Jewell County Monitor, Mankato, KS, Thu., June 12, 1913.

- ↑ The Solomon Tribune, Solomon, KS, Thu., May 29, 1919.

- ↑ Brooklyn Eagle, Brooklyn, NY, Wed., June 4, 1919.

- ↑ The Kansas City Post, Kansas City, MO, Sun., June 1, 1919.

- ↑ Springfield Leader and Press, Springfield, MO, Wed., June 11, 1919.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Thu, Jan. 6, 1921.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Apr. 15, 1924.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Dec. 18, 1928.

- ↑ The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Jan 1, 1929.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Mon., June 20, 1938.

- ↑ The Mercury, Manhattan, KS, Tue., Mar. 14, 1933.

- ↑ The Morning Chronicle, Manhattan, KS, Thu., May 11, 1933.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sun., July 30, 1933.

- ↑ The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, Sun., July 23, 1933.

- ↑ The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Jan. 10, 1982.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Fri., Nov 15, 1968.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Wed., Sep 10, 1969.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Sep. 6, 1977.

- ↑ The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, MO, Mon., Jan. 4, 1982.

- ↑ The Springfield News-Leader, Springfield, MO, Thu., Dec. 15, 1988.